Proceedings of a court of record

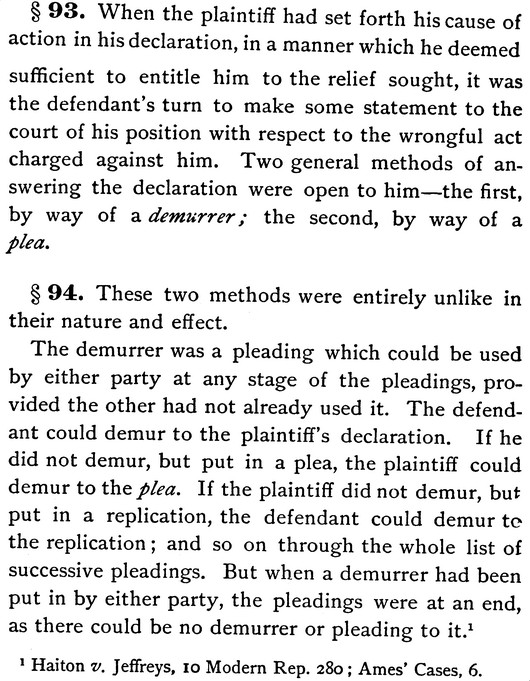

Now that it is established what a common law form of action is and the particulars of the form of action Trespass on the Case to obtain remedy for a hindrance to a common law name change, at common law, after service of the action, the defendants have the opportunity to either plea, to raise objections based on perceived insufficiencies or wrongful statements in the served action, or they could demur, admit all facts were correct and to raise a question of law for the tribunal to decide. If they chose the first, to raise objections, then this set in motion a series of letters or statements served or said back and forth between the plaintiff and defendant:

• To resolve the facts of the case until they were no longer in dispute, and/or

• To prove that the statement of the wrongs done were false or inadequate.

Once this battle of words had ended, then the question of law was raised for the tribunal to decide. During all of this, if facts fell into an impassible dispute, a jury could be called to decide what facts were actually correct. As well, and as further ensured by the 7th Amendment, a jury could be called at any time to decided any matter of fact (and even of law). Post-revolution — similar to the check put on the crown with a jury of barons in the 61st chapter of the Magna Carta — to call a jury of twelve other sovereigns in a suit at common law is quite literally the only way to challenge the final decision of a sovereign’s tribunal in a court of record.

As shown earlier, common law courts, court of record, have unlimited jurisdiction, while civil courts such as “are courts of limited jurisdiction” [Stein vs. Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators, and Paper Hangers of America, DCCDJ (1950) 11 F.R.D. 153]. Chief Justice Marshall of the U.S. Supreme Court stated this fact clearly:

“The judgment of a court of record whose jurisdiction is final is as conclusive on all the world as the judgment of this Court [the U.S. Supreme Court] would be. It is as conclusive on this Court as on other courts. It puts an end to inquiry concerning the fact by deciding it.” Ex Parte Watkins, 28 U.S. 3 Pet. 193 193 (1830).

As such, if the defendant does feel errors have been made, there is no appeal to a higher court, for at common law, the highest court is the sovereign’s, and the defendant’s only recourse is to use the high prerogative writs themselves to recall the sovereign’s court into session for a re-trial.

This is the manner in which courts of record operate, many of the details of which are below.

As said above, after service of the action, several options were open to the defendant (McKelvey, 68-9):

Essentially, statements, or “pleadings,” occurred back and forth between defendant and plaintiff. A “plea” raised objections to facts and statements in the declaration, the demurrer admitted all things were correct at that point and generally constituted an asking for the court to give judgment. As shown above, it can be understood that ideally, virtually everything worth saying by the plaintiff about the situation, was put forward in statements within the form of action.

If a plaintiff wanted to not have to dispute any of the facts with the defendant, they would in their greatest honesty bring forth all the facts and wrongs of the case within the paperwork of their original action. Then there would be nothing left for the defendant to dispute, and the defendant would demur — for everything which the plaintiff could say, had already been said, and said well, in the paperwork. Ideally that is the best course of action, to make sure you state all of the facts up front as perfectly honestly as possible in the paperwork so your opponent will have nothing to dispute, except perhaps form.

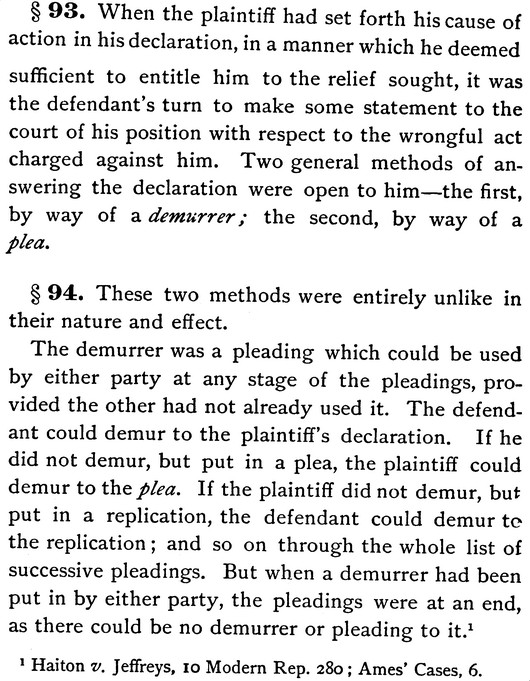

From the quote above, it also explains, “If the plaintiff did not demur, but put in a replication, the defendant could demur to the replication; and so on through the whole list of successive pleadings.” This “whole list” is theoretically infinitely long, and each plea in its order had a specific unique name/title, and though McKelvey and Perry do list many of them — as McKelvey said in his Preface (iii), it is the “main principles of the subject” which matter “for the purposes of the student who expects to practice in this country,” so not much fine detail is given. The principle is that, the pleas could go on theoretically forever, but didn’t usually go past the forth plea before a demurrer was submitted (McKelvey, 68):

Presently, many people follow the practice of titling their pleadings the answer and reply. Each successive plea would take a swing at their opponent, back and forth, back and forth, disputing the facts and arguments until one or the other gave up and demurred. Then upon the demurrer was judgment rendered.

The next quote by McKelvey (2-3) explains some of what makes a declaration sufficient and who can make objections to its insufficiency:

So to object to an insufficiency of a “statement of the plaintiff’s case” one must possess not merely “a knowledge of the principles of pleading”, but also a “knowledge of substantive law” (meaning a knowledge why and how one has rights, see Black, 1598), or in other words “a general knowledge of the rights and obligations of the individual as a member of civilized society subject to the common law, and of the different forms of action.” So if you do not know the common law and its various forms of action, if all one can quote are statutes and written rules, then one’s objections are relatively meaningless. Also from this statement, it is clear that magistrates do not raise objections or determine insufficiencies — “pleaders” do.

As well, it is clear that “the different forms of action [are the means by] which such rights and obligations are enforced,” informing one that when a dispute in common law arises, the way one enforces it is by using a common law action.

So, to tie it together, in a plea, when a pleader makes objections, they are made in regard in one’s knowledge of right and wrong in an evolved society, especially in the light of the logic of “good common sense,” all in relation to the clarity of the plaintiff’s statement that a right or rights have been violated.

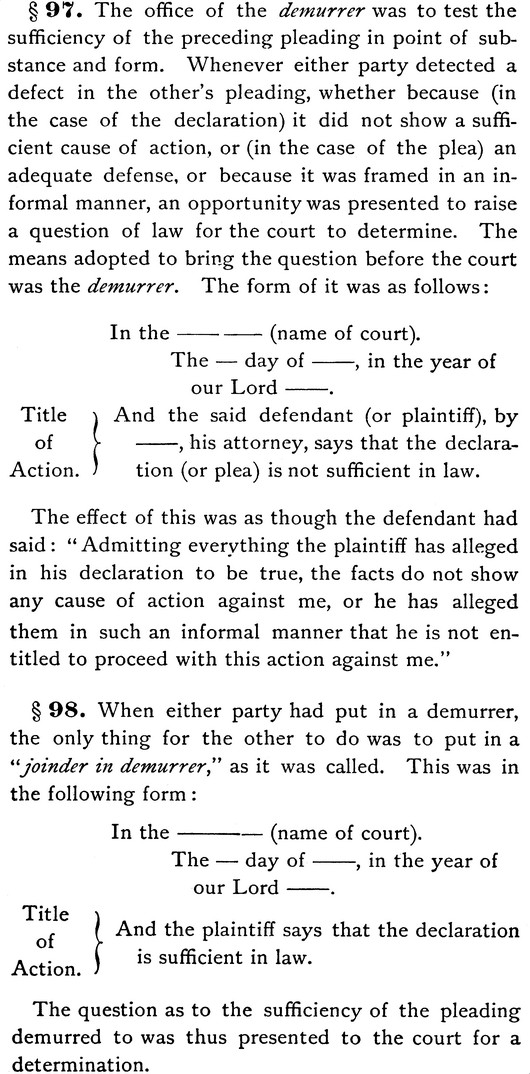

When the pleas had come to an end, then a demurrer was entered by one party or another. The demurrer itself specifically could do several things, but one thing in general (70-1):

So, the demurrer essentially admitted that all the facts put forth in the cause of action were true, but claimed that either the facts were “not sufficient” to show a breach of the law, or that they were so “informal,” not adequately fitting one of the ten forms of action in name and statements, that the claim did not qualify the plaintiff for relief.

McKelvey goes on (71-2):

So, originally, the demurrer was a “harsh” one shot deal. Once the other party demurred on any defect, the entire suit was thrown out. As this was at times rather unjust, common law proceedings evolved so that outside of the specific defects pointed out by the defendants, on all other points in the suit, the plaintiff would receive remedy.

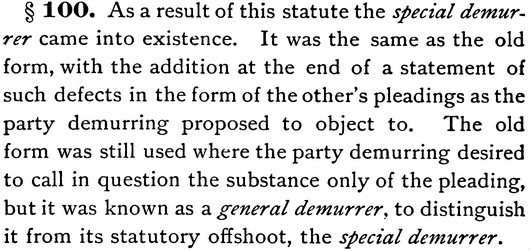

The statute above and its ancient date, 1585, reveal a number of things to us. Firstly, the ancient and time tested nature of the common law. Secondly, that as old as common law form is, its simplicity is its strength (for Trespass on the Case it must include: the wrongs done and the facts regarding those wrongs). Thirdly, that amid its simplicity, outside of failures of facts and form pointed out by a defendant, justice is administered “without regarding any imperfection, defect, or want of form in any ... pleading.” Which tells one that magistrates are not who are to make objections to form, but that the tribunal “shall proceed and give judgment according as the very right of the cause and matter in law shall appear unto them.” The tribunal is not to be a judge of form, nor is the magistrate. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, this reveals that form is not law, nor should form be a measure of law in the rendering of justice. We shall see shortly that the courts soon adapted so that not even calls on bad form affected judgment. Due to the statute above, soon a new kind of demurrer came into being called a special demurrer, vs. the old variety, a general demurrer. With this new demurrer one would specifically admit all facts were correct, but would make specific objections at the end concerning the form (72):

As much as this special demurrer might have helped a defendant to tear down a plaintiff’s suit based on form, in the next passage we see yet another evolution in common law proceedings, that soon it became such that, even when the defendant would point out defects in form, it could not stop justice, and judgment was rendered in favor of the plaintiff regardless of inadequacies in formal presentation (72):

Facts are the key. Not form. If one relies on defects in form, to point out a wrongly chosen form of action, a badly phrased statement of the wrong, etc. — if one was “to rely upon some defect in the other’s pleading instead of answering the facts set forth, final judgment was given against him.” The proceedings had evolved to be strictly about law and facts. The above passage also demonstrates the finality of a common law court’s decision, and the only way to possibly reverse such a decision was to petition the sovereign, or in the sovereign’s watchful eye he might step in directly to issue a high prerogative writ of error or of certiorari — the sovereign himself correcting a mis-step in one of his reflections.

The next quote, as well, shows the invariable uselessness of a defendant to demur based on form, versus to plea (73-4).

For a defendant to demur instead of to plea the facts actually appears to be a sign that the defendant really has no case, and that a wrongly titled action or a badly formed statement within it cannot hinder the plaintiff from receiving the remedy he seeks. Only a defendant challenging the facts can hope to turn the tide of a common law suit against him.